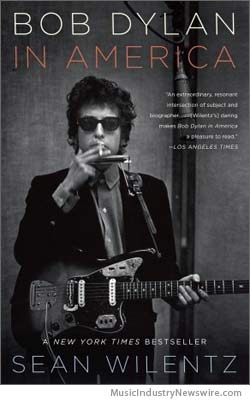

Book Review: ‘Bob Dylan in America’ by Sean Wilentz

MuseWire COLUMN: Smoothly written and dynamic, Sean Wilentz’ book is full of insight, commentary, and historical perspective about songwriting’s greatest poet. Like his subject, the work is reflection and refraction of fact, fancy, and fable.

Bob Dylan has created so many masterful poem-songs that it is sometimes difficult to keep track of them all. You can put on the vinyl, slide in the CDs, and scroll through the databank, and you will pleasingly, delightfully, assuredly swim through the decades of Dylan classics. But unless you start making your own list of annotations, it might be best to turn to a good biographer for some perspective.

Bob Dylan has created so many masterful poem-songs that it is sometimes difficult to keep track of them all. You can put on the vinyl, slide in the CDs, and scroll through the databank, and you will pleasingly, delightfully, assuredly swim through the decades of Dylan classics. But unless you start making your own list of annotations, it might be best to turn to a good biographer for some perspective.

Wilentz provides more than some perspective; he takes you on a veritable walking tour of Dylanania, bringing the best moments into sharp focus with a powerful jolt and with details so varied and intense that you almost feel embarrassed to have been caught eavesdropping on people’s conversations. Actually, it often gets to the point where you feel like you are inside some people’s thoughts.

Given extraordinary access to archival information, Wilentz grabs the data in both fists and turns it into a series of excursions into more than Dylan’s saga, but also the history of folk music, blues music, poetry, performing styles, touring, recording sessions, and even history itself.

You Are There

The chapter on the making of “Blonde on Blonde” is twenty-six pages of You Are There In The Studio and it is fascinating; very nearly worth the price of the book. Of course, it helps if you own, or at least have heard, that album; but either way, the images, the struggles, the fits and starts, the sounds, and the magic are captured and presented in ways both terrific and taut.

Since I think “Blonde” is a great and awesome rock record, that amount of attention seems justified. Wilentz obviously is impressed with the recording as well, and makes a number of pointed observations, including that the songs have a quality that goes beyond excellence to achieve a state of delicious delirium. He also notes that Dylan was “working in a 1960s mode of what T.S. Eliot had called, regretfully, the dissociation of sensibility — cutting off discursive thought or wit from poetic value, substituting emotion for coherence.”

Good Questioner

As an interviewer, Wilentz is terrific. There are many wonderful comments from people throughout Dylan’s personal and professional life. Returning to the “Blonde” section as an example, Wilentz shares quite a few conversations from people who were on those sessions or in the studio at the time, including Al Kooper, Charlie McCoy, producer Bob Johnston, and even Kris Kristofferson, who at that point was working as a janitor at the studio. Wilentz delves deeply into all aspects of the recording dates, even going so far as to note that Rick Danko, Bobby Gregg, and Paul Griffin played on the album but were never listed on the credits for either the vinyl or CD releases.

Refraction

Wilentz comes at his subject from all sides, presenting Dylan now, then, before, after, and in the perspective of antiquity. It’s an ambitious goal and I think he pulls it off. What could so easily have turned into a crazy quilt patch-work has emerged as a multi-faceted jewel of a book.

His method comes with consequences, as this approach might not hold the full attention of the average fan. In the interest of placing some of Dylan’s creative choices in social context, Wilentz devotes sections of the book to events and people one might not have expected, including Aaron Copland, Blind Willie McTell, and Marc Blitzstein. The more anticipated names such as Woody Guthrie, Jack Kerouac, Joan Baez, Allen Ginzberg, Pete Seeger, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and so on, are well-represented, but Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby figure in the story a whole lot more than you might have predicted. A discussion of the Beats vs. the Folkies is one thing, but Old Blue Eyes and Der Bingle? Yup, and all of Wilentz’ observations hold up upon reflection.

Influences on Dylan include the early days of broadcast television as well as a host of literary and music figures, including William Blake, Ovid, Robert Johnson, Lotte Lenya, Gene Autry, Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Leonard Bernstein, Ezra Pound, William S. Burroughs, and Charlie Chaplin. To name a few.

Perspective

There are lots of great stories here. Example: Dylan’s first concert in New York was deemed disappointing as “only fifty-three ticket buyers showed up.” Up-and-coming acts in Los Angeles today would probably kill to draw half that. Later on, when he was booked to perform on the highly rated Ed Sullivan Show, which aired on the CBS network Sunday evenings, Dylan made “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues” his song choice. As you might expect, the CBS executives had some sort of minor stroke and ordered him to sing something else. Rather than be censored, Dylan left without appearing on the program.

Sense of Time and Place

Performing at Philharmonic Hall in 1964, Dylan debuted “Gates of Eden” and “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” and Wilentz takes us there. . .

During these performances, the audience was utterly silent, trying at first to catch all the words, but finally bowled over the by intensity of both the lyrics and Dylan’s playing, even when he muffed a line. We would not get the chance to figure the songs out for another five months, when they appeared on

Bringing it All Back Home — and even then it would take repeated listening for any of it make sense. At the time, it just sounded like demanding poetry, at times epic narrative, proving once again that Bob Dylan was leading us into new places, the exact destination unknown but still deeply tempting.

Rolling Thunder

There is a forty-page section dealing with the Rolling Thunder Revue and the story of “Hurricane” (both the song and the relevant details of Ruben “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer who was falsely convicted of murder), with side-trips into traveling circuses and Les enfants du paradis (“Children of Paradise”) the 1945 film by Marcel Carne and Jacques Prevert. Does the book waver in its forward flow because of all this? Nope. You’ll be swept right along, possibly the way Dylan was when he encountered these events in real life.

Beg or Borrow

Thanks to Wilentz persistence, it feels like we finally get the whole story involving the discussions and arguments regarding Dylan’s borrowing, fair use, plagiarism, or “Love and Theft,” which is both a Dylan album and a chapter in the book. In discussing Dylan’s song “Cross the Green Mountain” from the film “Gods and Generals,” Wilentz writes:

… the song lifted a line from the poem “Charleston” by the almost completely forgotten Confederate poet Henry Timrod. But Dylan’s borrowings were actually much more extensive. “Cross the Green Mountain” included lines and images from sources that ranged from Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Henry Lynden Flash’s “Death of Stonewall Jackson,” and Nathaniel Graham Shepherd’s “Roll-Call,” to Frank Perkins and Mitchell Parish’s jazz standard from 1934, “Stars Fell on Alabama.” In the next-to-last verse, Dylan condensed an entire Walt Whitman poem, “Come Up from the Fields, Father,” about the news of a young man’s falling in combat reaching home, in a single, compact eight-line stanza, and he took a phrase from Whitman’s original to boot.

The situation is dealt with in scholarly and gentlemanly fashion, as one might expect from the historian-in-residence for Dylan’s official website. Quite apart from the fact that most of the sources are in the public domain, there is the transformative value of the newly-created work.

For more than half a century, Bob Dylan had been absorbing, transmuting, and renewing and improving American art forms long thought to be trapped in formal conventions. He not only “put folk into bed with rock,” as Al Santos still announces before each concert; he took traditional folk music, the blues, rock and roll, country and western, black gospel, Tin Pan Alley, Tex-Mex borderlands music, Irish outlaw ballads, and more and bent them to his own poetic muse.

Unexpected Discography

Instead of Dylan’s discography, which is widely available online, Wilentz gives us six full pages of songs that influenced Dylan, from Roy Acuff’s “Wait for the Light to Shine” to Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Your Funeral and My Trial.” Like Dylan the alchemist (for that, ultimately, is what Wilentz proclaims him), the list is fascinating.

Portrait

The prose that Wilentz employs is witty, deft, expressive, and as you can see here in his overview of “Love and Theft” (the album not the concept), often lyrical:

And with his expert timing, better than ever, Dylan shuffles space and time like a man dealing stud poker. One moment it’s 1935, high atop some Manhattan hotel, then it’s 1966 in Paris or 2000 in West Lafayette, Indiana, or this coming November in Terre Haute, then it’s 1927, and we’re in Mississippi and the water’s deeper as it comes, then we’re thrown back into biblical time, entire epochs melting away, except that we’re rolling across the flats in a Cadillac, or maybe it’s a Ford Mustang, and that girl tosses off her underwear, high water everywhere.

Wilentz paints a portrait of Dylan in nouns, verbs, and adjectives revealing him as a product of black-and-white TV, Beat poets, rebels, street artists, hustlers, outcasts, social protesters, folkies, hot rodders, carny performers, singers of all genres, and the stacks of the New York Public Library. Considering the varied ‘n’ sundry topics Wilentz covers in this work, an alternate title might have been “America in Bob Dylan.” Either way, a terrific read.

Book Summary

“Bob Dylan in America” by Sean Wilentz;

Doubleday, Hardcover, 400 pages, 100 photographs, ISBN: 978-0-385-52988-4, $28.95; Paperback, ISBN: 978-0-7679-3179-3, $16.95;

* http://www.randomhouse.com/author/81426/sean-wilentz?sort=best_13wk_3month

* http://www.boblinks.com

* http://www.expectingrain.com

VIDEO: “Positively 4th Street”

http://youtu.be/j2wuPssClKs

Article Copr. © 2011 by John Scott G, originally published on MusicIndustryNewswire-dot-com before the site was revamped as MuseWire.com in March 2015 – all rights reserved. Disclosure: No fee or other consideration was provided to the author of this article, this site or its publisher by the book author, publisher or any agency.

Jan 13, 2012 @ 9:24 PM PST

I read another review of this Dylan book…er, somewhere. But yours is better.